“

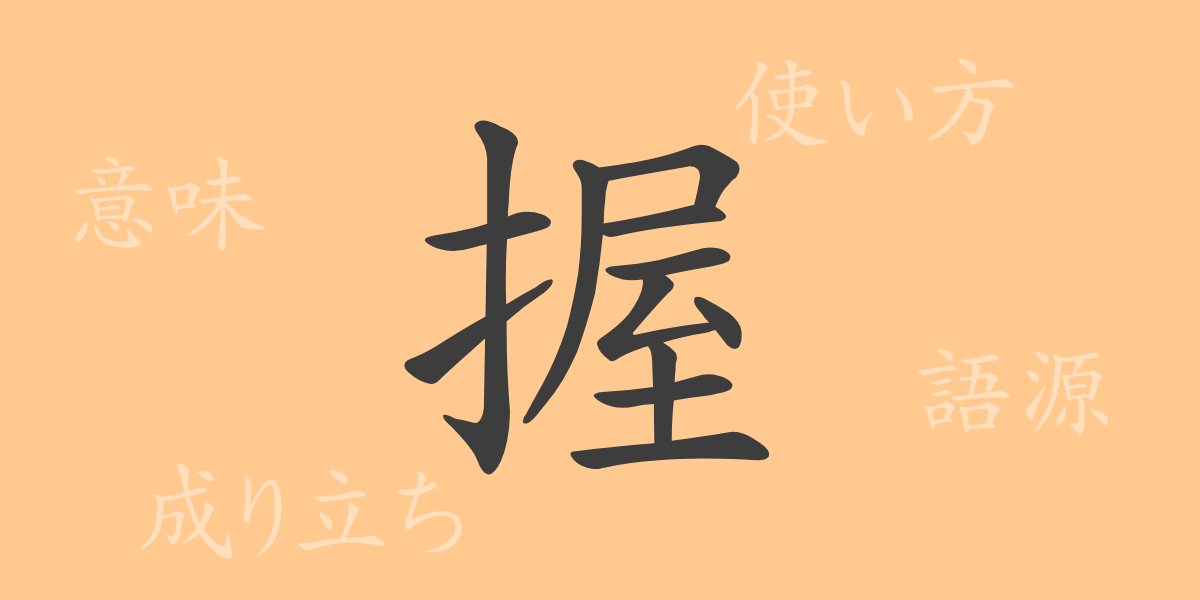

The Japanese language contains thousands of kanji (characters), each with its own distinct history and meaning. In this article, we focus on one commonly used character in everyday life: 「握」(Aku / Nigi-ru), which evokes the image of firmly holding something in one’s hand. This character is closely associated with strength and connection in language. We will explore the origin, readings, meanings, and cultural roles of 「握」(Aku) in Japanese society.

Origin of 握 (Aku) – Etymology

The kanji 「握」(Aku) is made up of the radical 「扌」(Te-hen, meaning “hand”) and the component 「屋」(Oku), which signifies strength or enclosure. Together, they visually represent the act of grasping something firmly with one’s hand. This character originated in ancient China and was later adopted into Japanese, where it has developed its own unique readings and usages over time.

Meaning and Usage of 握 (Aku)

「握」(Aku) primarily means “to grip” or “to hold” (Nigi-ru). It refers to the physical act of grasping something tightly with the hand. Figuratively, it can also express the idea of holding power, control, or fate in one’s grasp. Common usages include words like 「握手」(Akusyu, handshake) and 「握り寿司」(Nigirisushi, hand-formed sushi), where the action of shaping or holding something by hand is central.

Readings, Stroke Count, and Radical of 握 (Aku)

The kanji 「握」(Aku) has several readings and structural features in Japanese:

- Readings: On’yomi : Aku; Kun’yomi : Nigi-ru, Nigi-ri

- Stroke count: 12 strokes

- Radical: 「扌」(Tehen, hand radical)

Common Idioms, Compound Words, and Sayings Using 握 (Aku)

There are many idioms, compound words, and proverbs in Japanese that include 「握」(Aku). Here are a few notable examples:

- 握手 (Akusyu): A handshake, used as a gesture of greeting or friendship between people.

- 握力 (Akuryoku): Grip strength; metaphorically, it can also represent strong willpower.

- 握り寿司 (Nigirisushi): A type of sushi made by hand-shaping rice and topping it with seafood.

- 一握の砂 (Ichiakunosuna): “A handful of sand,” symbolizing a small quantity or the fragility of life, inspired by the poetry of Takuboku Ishikawa.

- 命を握る (Inochiwonigiru): “To hold someone’s life,” meaning to have control over someone’s fate or life.

Conclusion on 握 (Aku)

The kanji 「握」(Aku) has long symbolized strength and determination, from its formation to its modern-day use. Though often used unconsciously in daily conversation, it holds deep historical and cultural significance. Its usage in expressions and idioms highlights the richness of the Japanese language. Through 「握」(Aku), we gain insight into the power contained in the human hand and the depth of meaning found in even a single character.

“